question

dict | answers

list | id

stringlengths 1

6

| accepted_answer_id

stringlengths 2

6

⌀ | popular_answer_id

stringlengths 1

6

⌀ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

{

"accepted_answer_id": null,

"answer_count": 0,

"body": "I've seen this a few times and always just been guessing the meaning. I have\nthis dialogue were 勝てはしない is said. Is ...てはしない used for emphasis? Saying that\nwinning can't be done?\n\nI'm just curious why I never read about this grammar in my books or anywhere\nelse. Is it like saying it is impossible? Like 勝ち得ない or something. I'd like\nyour help. Dialogue under with my attempted translation.\n\n深海王を狩るつもりならやめておけ If your intention is about to hunt the deep sea king leave it\nfor me\n\n深海王? The deep sea king?\n\nヒーローごときが束になっても勝てはしない Even if heroes bunch together we can't win",

"comment_count": 1,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-09T13:49:57.263",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42372",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-09T13:49:57.263",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "7713",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 1,

"tags": [

"grammar"

],

"title": "~てはしない form grammar",

"view_count": 173

} | []

| 42372 | null | null |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42378",

"answer_count": 2,

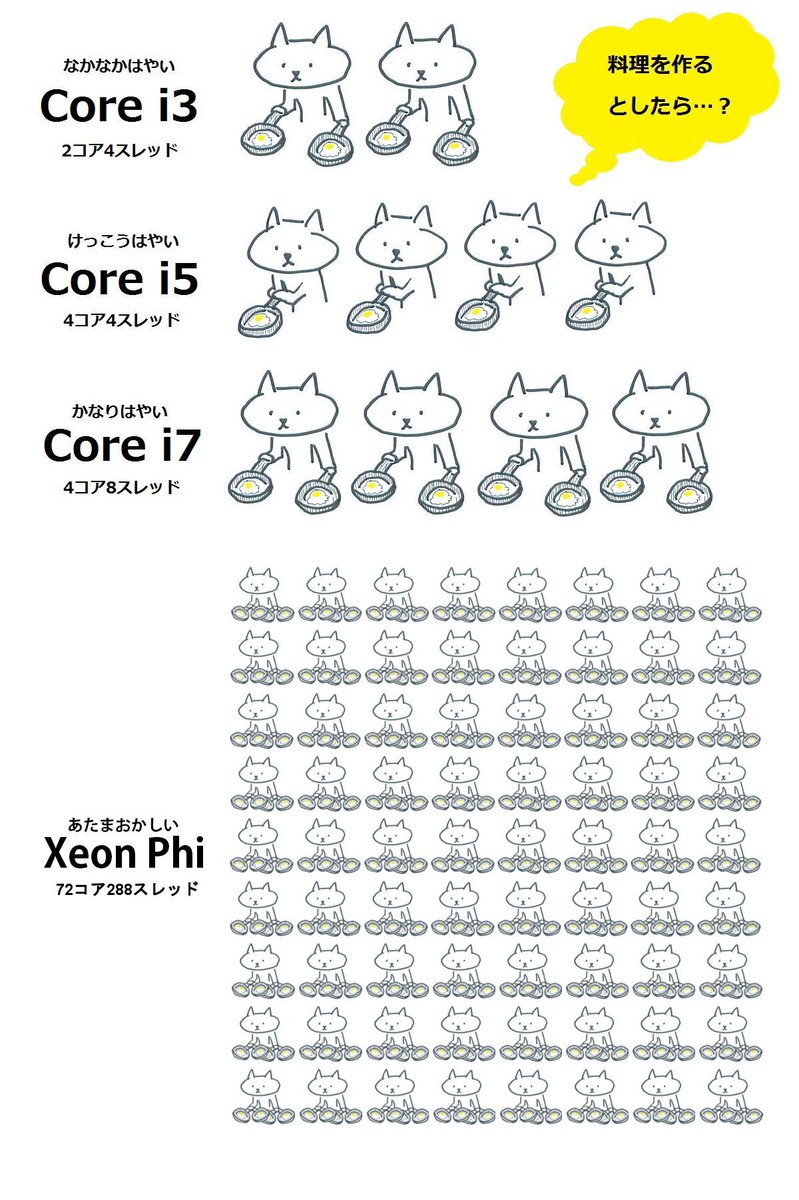

"body": "Recently, I found a [joke about CPU Cores/Threads\nhere](https://twitter.com/P5QPRO/status/818421589930745859). I catch attention\non the word \"あたまおかしい\" which in this context is probably:\n\n> It is **crazily/insanely** fast.\n\nRight? But I have seen many use of \"Okashii\" alone that means \"weird\". So many\nquestions regarding this phase follow:\n\n 1. Can \"あたまおかしい\" in the above article, in any way, can it be translated to **too fast that head is dizzy/weird**? Instead of \"mentally\" craziness.\n\n 2. Are \"頭おかしい\" and \"頭がおかしい\" have the same meaning and usage?\n\n 3. I wonder if this phase can describe dizziness in your head. Like, you say this to your friend when your head feels weird or dizzy? \"ああ、頭がおかしくなる。\"\n\n",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-09T15:14:44.563",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42373",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-09T18:55:17.763",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-09T17:22:30.020",

"last_editor_user_id": "5010",

"owner_user_id": "19345",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 2,

"tags": [

"meaning",

"slang",

"internet-slang"

],

"title": "Using of あたまおかしい in various situation and translation",

"view_count": 1050

} | [

{

"body": "> can it be translated to too fast that head is dizzy/weird? Instead of\n> \"mentally\" craziness.\n\nNo, あたまおかしい means _crazy/insane/mad_ , not _dizzy_. Its basic meaning is of\ncourse negative, but recently あたまおかしい has gained a positive sense, as seen in\nthis picture. You can say あたまおかしい is mostly positive when this word is used\nfor comedians, \"crazy\" YouTube video, etc.\n\nおかしい just means _weird/strange/peculiar_ as well as _funny_. If it were not\nfor あたま in this picture, it would not make much sense.\n\n> Are \"頭おかしい\" and \"頭がおかしい\" have the same meaning and usage?\n\nAs net slang, あたまおかしい is used almost like a single i-adjective. あたまがおかしい might\nmean the same thing depending on the context, but I rarely see it. Since\nあたまがおかしい is not an established slang term, I think it tends to be used in the\noriginal (i.e., negative) sense.\n\nあたまおかしい is still net slang, especially when this means something positive. A\nsafer replacement would be\n[ヤバい](http://jisho.org/word/%E3%82%84%E3%81%B0%E3%81%84), which is a widely\nknown slang term that can also be both positive and negative.\n\nPeople often add `(ほめ言葉)` to clarify it has a positive connotation. e.g,\n\"narutoさん頭おかしい(ほめ言葉)\"\n\n> I wonder if this phase can describe dizziness in your head. Like, you say\n> this to your friend when your head feels weird or dizzy? \"ああ、頭がおかしくなる。\"\n\nYou should say\n頭が[くらくら](http://jisho.org/word/%E3%81%8F%E3%82%89%E3%81%8F%E3%82%89)する or\n頭がぐらぐらする to express dizziness. 頭がおかしくなる usually means \"I'm going mad\".",

"comment_count": 2,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-09T17:21:12.377",

"id": "42378",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-09T18:22:34.893",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-09T18:22:34.893",

"last_editor_user_id": "5010",

"owner_user_id": "5010",

"parent_id": "42373",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 3

},

{

"body": "Just to add, the translation of your pic wouldn't be \"Insanely/Crazily fast\",\nbut literally just \"Insane/Crazy\". I think it's worth making the distinction\nthat this (slang) usage of \"insane/crazy\" does not coincide with the usage in\nthe English (slang) language.\n\nIn English, when someone says, \"That's crazy/insane!\" (of course, depending on\nthe context and tone) it would mean pretty much the same as \"That's awesome!\".\n\nWhen used in this context, 頭(が)おかしい would have the tone of \"ridiculous\"\nor\"whoever is going this far has to be stupid/out of his mind\". So as you can\nsee, it is not really praising the target, though in turn it does in a\nroundabout way. Think of it as needing one extra step to become praise.\n\n> That's crazy! → That's cool! (direct praise) \n> 頭おかしい! → He's out of his mind for doing that! → It's so ridiculous, it's\n> cool! (indirect praise)\n\nAlso note that this type of praise is only really used in extreme situations,\nlike the example you gave.\n\n> A: \"My friend painted this really good picture.\" \n> ○B: \"That's crazy!\" \n> ×B: 頭おかしいわ(褒め言葉)\n\nNotice that even with the connotation note, it's not extraordinary enough and\nmost likely other people would reply with \"What's so crazy about it?\". Compare\nthat to the English usage, which is generally acceptable.\n\n> A: \"My friend painted this really good picture using only his mouth to hold\n> the brush!\" \n> ○B: \"That's crazy!\" \n> ○B: 頭おかしいわ(褒め言葉)\n\nBasically, it's best to use in situations you feel would be overkill.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-09T18:55:17.763",

"id": "42384",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-09T18:55:17.763",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "9508",

"parent_id": "42373",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 3

}

]

| 42373 | 42378 | 42378 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42377",

"answer_count": 1,

"body": "I cannot get what な means in the following sentence.\n\n> 彼女はそれがいくら **な** のかわかります。\n\nCouldn't it be written 彼女はそれがいくらのか分かります?",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-09T16:12:04.487",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42375",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-09T18:31:31.590",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-09T18:31:31.590",

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "17380",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 0,

"tags": [

"syntax",

"copula"

],

"title": "What is な role here?",

"view_count": 59

} | [

{

"body": "Because いくら is not a verb, the の of のか cannot directly follow it; な acts to\nlink the two.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-09T16:53:02.220",

"id": "42377",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-09T16:53:02.220",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "9971",

"parent_id": "42375",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 1

}

]

| 42375 | 42377 | 42377 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42379",

"answer_count": 1,

"body": "I noticed this when I was listening to Momoiro Clover Z's 「行くぜっ!怪盗少女」, which\nhad this line: 「土日{どにち}はよろしくね 週末ヒロインです」. I understand that 土日 means 土曜日 + 日曜日\n= weekend, i.e. 週末. Thus, can 土日 and 週末 be used interchangeably, or are there\ndifferent nuances in 土日 and 週末?\n\nThere is also the term 休日, which I understand as referring to \"days off\", i.e.\nweekends plus public holidays 祝日. However, can 休日 be used interchangeably with\n週末/土日 as well? (Because I think I might have seen this usage in Japan, but I\nmay be wrong.)",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-09T16:31:24.827",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42376",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-09T17:49:46.963",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-09T16:37:09.803",

"last_editor_user_id": "19346",

"owner_user_id": "19346",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 5,

"tags": [

"word-choice",

"usage"

],

"title": "The usage of 土日, 週末 and 休日",

"view_count": 704

} | [

{

"body": "土日 and 週末 are very similar, but 週末 vaguely refers to weekend, while 土日 is\nexplicitly Saturday and Sunday. Friday nights are usually considered as part\nof 週末, but not part of 土日. While 週末ヒロイン sounds like a nice coined phrase,\n土日ヒロイン sounds a bit too strict and funny to me. Travel magazines often have\narticles titled ~で週末を楽しむ, but usually not ~で土日を楽しむ.\n\n休日 refers to days off. You don't necessarily have to have days off on\nSaturdays and Sundays, so 休日 is different from 土日/週末.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-09T17:49:46.963",

"id": "42379",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-09T17:49:46.963",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "5010",

"parent_id": "42376",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 9

}

]

| 42376 | 42379 | 42379 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42383",

"answer_count": 1,

"body": "> \"Evaluation of practical experience (=internship) and it's contribution\"\n\nI would use something like this:\n\n> 「実習【じっしゅう】評価【ひょうか】及び【および】その貢献【こうけん】」\n\nI could be relatively satisfied (but just partly) with 実習【じっしゅう】 as for\n\"practical experience\" and 評価【ひょうか】 as for \"evaluation\", but I feel\nuncomfortable by using 貢献【こうけん】 as for \"contribution\". I haven't used 貢献【こうけん】\nbefore and haven't used yet any other alternative meaning for the word\n\"contribution\".",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 4.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-09T18:12:41.150",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42380",

"last_activity_date": "2021-11-07T22:20:45.667",

"last_edit_date": "2021-11-07T22:20:45.667",

"last_editor_user_id": "30454",

"owner_user_id": "9364",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 0,

"tags": [

"english-to-japanese"

],

"title": "\"Evaluation of practical experience (=internship) and it's contribution\"",

"view_count": 64

} | [

{

"body": "Contribution can be translated either as 貢献(度) and 寄与【きよ】(度).\n\n * 貢献: beneficial contribution from people (by money, labor, source code, etc)\n * [寄与](http://eow.alc.co.jp/search?q=%E5%AF%84%E4%B8%8E): contribution of various inanimate factors (e.g., price, demand, temperature, ...). (can be positive or negative)\n * ~度: value, degree\n\nIf you are asking how much the \"practical experience\" has affected something,\n寄与度 is probably the best choice.\n\nI don't know the context, but \"practical experience\" can be translated\n[differently](http://eow.alc.co.jp/search?q=practical%20experience&ref=sa).\nPlease make sure 実習 is the right translation in the context in question.",

"comment_count": 2,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-09T18:52:41.927",

"id": "42383",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-09T18:52:41.927",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "5010",

"parent_id": "42380",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 2

}

]

| 42380 | 42383 | 42383 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42430",

"answer_count": 1,

"body": "A comment in one of my previous questions ([Why is a verb in the past (た形)\ncontradicted with\n~ていない?](https://japanese.stackexchange.com/questions/42242/why-is-a-verb-in-\nthe-past-%e3%81%9f%e5%bd%a2-contradicted-\nwith-%ef%bd%9e%e3%81%a6%e3%81%84%e3%81%aa%e3%81%84)) contained the following\nsentence (fragment?):\n\n> 言われてみると不思議...。\n\nI'm not entirely certain what this means but going from context, I'd guess\nmaybe something along the lines of \"It'd be odd if you tried to say it (like\nthat)...\"\n\nI'm having difficulty understanding the changing voice (active/passive) in the\nverb 言われてみる. **Is this expression active or passive (or both for that\nmatter)?**\n\nIn addition, how would the meanings of the following differ (if the second and\nthird are valid of course):\n\n> 1. 言われてみる\n> 2. 言ってみられる\n> 3. 言われてみられる\n>",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-09T18:44:09.747",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42382",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T23:48:15.747",

"last_edit_date": "2017-04-13T12:43:44.260",

"last_editor_user_id": "-1",

"owner_user_id": "3296",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 4,

"tags": [

"nuances",

"verbs",

"passive-voice"

],

"title": "Passive Verb + みる",

"view_count": 201

} | [

{

"body": "> 「言{い}われてみると不思議{ふしぎ}...。」\n>\n> I'd guess maybe something along the lines of \" _ **It'd be odd if you tried\n> to say it (like that)...**_ \"\n\nNot really, it is not the speaker who said something here because 「言われる」 is\npassive voice. **Another person told you something and you realize that it is\nindeed odd (even though you have never given the matter much thought\nbefore.)**\n\n> I'm having difficulty understanding the changing voice (active/passive) in\n> the verb 言われてみる. Is this expression active or passive (or both for that\n> matter)?\n\nGrammatically, the 「言われて」 part is passive and the 「みる」 part is active. More\nstrictly speaking, however, 「みる」 here is only a subsidiary verb; therefore, it\nis only active in name, so to speak. The real verb here is 「言われる」, which is\n100% passive. Thus the expression 「言われてみる」 is basically passive voice. At\nleast, as I said above, it is not the speaker who said something.\n\n> \"Now that you mention it ...\"\n\nwould be the usual translation.\n\nFinally, regarding the three expressions you listed at the end, 「言ってみられる」 and\n「言われてみられる」 (#2 and #3) do not make sense.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T23:42:49.160",

"id": "42430",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T23:48:15.747",

"last_edit_date": "2020-06-17T08:18:27.500",

"last_editor_user_id": "-1",

"owner_user_id": null,

"parent_id": "42382",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 2

}

]

| 42382 | 42430 | 42430 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42402",

"answer_count": 2,

"body": "I was translating a text from my textbook and I can't understand the meaning\nof なら in these two phrases.\n\n> 1. メンバーを1人紹介するなら?\n> 2. 逆にお兄さんに紹介するなら?\n>\n\nCan someone translate this for me, so I can understand it?",

"comment_count": 2,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-09T19:52:29.110",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42385",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T01:12:27.673",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-09T19:57:05.323",

"last_editor_user_id": "1628",

"owner_user_id": "19349",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 0,

"tags": [

"grammar",

"translation",

"conditionals"

],

"title": "What does なら mean in メンバーを1人紹介するなら?",

"view_count": 296

} | [

{

"body": "In general **なら** means \"if\", but can sometimes be loosely translated to mean\n\"in the case that\" when it is at the end of a sentence.\n\n`メンバーを1人紹介するなら?`\n\n_(What do you do/Who will you introduce) **in the case** that you are\nintroducing a member?_\n\n`逆にお兄さんに紹介するなら?`\n\n_(What do you do/Who will you introduce) **in the case** that you are instead\nintroducing him/her to your older brother?_\n\nNote that in both of these sentences you could also just say \"If you're\nintroducing one member?\" \"If you're introducing them to your brother?\"\n\nI don't really know the context of the sentences but なら in this case means \"If\nyou are going to do\" what proceeds before it\n\nなら in general can mean \"if\" but it differs from ば and たら in that it isn't\npurely conditional\n\n`日本に行くなら横浜がいい`\n\n_\"If you're going to Japan you should go to Yokohama / Yokohama is good\"_\n\nMore literally put, \"If it is that you are going to Japan / In the case that\nyou're going to Japan, Yokohama is good\"",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T03:49:02.567",

"id": "42402",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T01:12:27.673",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-11T01:12:27.673",

"last_editor_user_id": "10300",

"owner_user_id": "10300",

"parent_id": "42385",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 3

},

{

"body": "In this case, なら means \"if\" or \"in the case that\". Here your sentences mean:\n\n> メンバーを1人紹介するなら(誰を紹介しますか)? \n> If you were going to introduce one member (...who would you introduce)?\n>\n> 逆にお兄さんに紹介するなら(誰を紹介しますか)? \n> Conversely, if you were going introduce to your brother (...who would you\n> introduce)?\n\nLike a lot of Japanese sentences, it is incomplete and there is an implied\nmeaning that you are expected to read. Usually, the sentence structure V + なら?\nindicates a repeat of the the verb along with a who/what/which.\n\n> この中からゲームを一つ選ぶなら? \n> If you were going to pick from one of these games (which one would it be)?\n>\n> 来週、一日だけ休めるなら? \n> If you could only rest one day next week (what day would it be)?\n\nNote that the structure only works with choices. I'm not a grammar expert, so\nI can't say I'm 100% right about the way it goes, but at least the\ntranslations should help. Also, from experience, this sentence structure isn't\ncommon in conversation; you would be expected to complete the sentence. It's\nmore of a questionnaire question.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T19:40:16.083",

"id": "42425",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T19:40:16.083",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "9508",

"parent_id": "42385",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 2

}

]

| 42385 | 42402 | 42402 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42395",

"answer_count": 1,

"body": "I've come across this phrase\n\n> 今の一撃を素直に食らっておけば、楽に死ねたのにね\n\nand I think it translates to something like: \"if you had taken that attack\nobediently, you would have died in peace\", but I can't really understand that\n死ねた: is it potential? a past of some sort? I can't really tell. And, moreover,\nisn't ておけば the ておく form + conditional (the if clause), so it's probably wrong\nmy translation in the past. Or is it some kind of future in the past? in the\ncontext she did just dodge an attack. I'm quite confused.",

"comment_count": 4,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-09T20:14:21.157",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42386",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T02:13:00.067",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-09T21:03:03.643",

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": null,

"post_type": "question",

"score": 3,

"tags": [

"potential-form",

"past"

],

"title": "what form 死ねたのに is?",

"view_count": 157

} | [

{

"body": "> 「今{いま}の一撃{いちげき}を素直{すなお}に食{く}らっておけば、楽{らく}に死{し}ねたのにね。」\n\nThis sentence is in a **_conversational/informal_** form of the English \"If ~~\nhad ~~, ~~ would/could have ~~\". That is why the tenses might look loose to\nsomeone who has studied with textbooks.\n\nThis person has **_not_** died yet.\n\n「死ねた」 here means 「死ねたはずだった」、「死ねたであろう」 = \" ** _would/could have died_** \"\n\n> \"Had he received that one blow with no protection, he would have been able\n> to die without pain.\"",

"comment_count": 1,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T02:13:00.067",

"id": "42395",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T02:13:00.067",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": null,

"parent_id": "42386",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 4

}

]

| 42386 | 42395 | 42395 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": null,

"answer_count": 3,

"body": "I know they are both used for comparisons, i.e. \"as X...\", \"for a X....\", but\nI don't understand the difference between them.",

"comment_count": 2,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-09T22:24:16.007",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42387",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T18:27:09.567",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-11T18:27:09.567",

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "19109",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 6,

"tags": [

"grammar",

"word-choice",

"particle-に",

"particle-と"

],

"title": "What is the difference between にしては and としては?",

"view_count": 2150

} | [

{

"body": "Xにしては is closer to \"for\" and としては is closer to \"as\"\n\n```\n\n 25歳としてもこれは難しい... \n \n```\n\n_Even as a 25 year old, this is hard_\n\n```\n\n 25歳にしてもこれは難しい... \n \n```\n\n_Even for 25 year olds, this is hard_\n\nThere is a different level of closeness to the expression, where にしては is more\ngeneral. In the above example, it would mean \"For those who are 25\" as opposed\nto としては which refers to the state of being 25 more than the group of 25 year\nolds.\n\nIt is also worth noting that として always follows a noun whereas にして can follow\na verb or verb clause.\n\n```\n\n 初めてケーキを作ったにしては、上手にできましたね。\n \n```\n\n_For somebody who is making a cake for the fist time, she did it very well_\n\nThe difference might be easier illuminated if we were to try to translate the\nfollowing:\n\n\"As someone who likes jazz, I'm glad I came to this party.\"\n\n```\n\n ジャズ好きとしては、このパーティに来てよかった\n \n```\n\n\"For people who like jazz, this is a good party.\"\n\n```\n\n ジャズ好きにしては、このパーティがいい\n \n```",

"comment_count": 2,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T04:00:04.233",

"id": "42403",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T04:43:44.187",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-10T04:43:44.187",

"last_editor_user_id": "10300",

"owner_user_id": "10300",

"parent_id": "42387",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 0

},

{

"body": "> A にしては B.\n\nSuppose the situation that the fact A generally leads the negative fact B, but\nnot the expected negative fact B but the affirmative fact B is true. Then we\nsay \"Aにしては、Bだ。\"\n\n> exampl-1: \"来日後3か月にしては、彼女の日本語は上手(じょうず)だ。\" \n> exampl-2: \"来日後10年にしては、彼の日本語は上手ではない。\"\n>\n> exampl-1: \"来日して(まだ)3か月なのだから、日本語は上手ではないだろう。しかし、それにしては、彼女の日本語は上手だ。\" = \"She has\n> come to Japan only for three months, so I expect she is still not good at\n> speaking Japnese, but contrary to my expectation, she is already a good\n> Japanese speaker.\" \n> exampl-2: \"来日して(もう)10年なのだから、日本語は上手だろう。しかし、それにしては、彼の日本語は上手ではない。\" = \"He has\n> come to Japan for ten years long, so I expect he is fairly good at speaking\n> Japanese, but contrary to my expectation, he is poor at speaking Japanese.\"\n\n\"にしては\" of the above examples means \"although.\"\n\n* * *\n\n> A としては B.\n>\n> exampl-3: \"来日して3か月の外国人としては、彼女の日本語は上手だ。\" \n> exampl-4: \"来日して10年の外国人としては、彼の日本語は上手ではない。\"\n\nThe above examples are natural and have the same meaning of exapmple-1 and\nexample-2 respectively.\n\nThe word \"としては\" requires a person, an attribute of person (means person\nitself) or an obstacle, and has more meaning than \"にしては.\"\n\n> \"子供が学校でいじめられている。親としては黙っていられない。\" = \"My child is bullied by his class mates.\n> As his parent, I won't remain silent.\"\n>\n> \"25歳としては、大人げない態度だ。\"= \"25歳の人間としては、大人げない態度だ。\" = \"His attitude is poor for the\n> twenty five years adult.\"\n>\n> \"誕生日にライフルを贈る親がいる。プレゼントとしては不適切だ。\" = \"Some parents give their child a rifle as\n> a birthday gift. It's extremly inappropriate as a brthday gift.\"\n\n* * *\n\n> \"A にしては B” \n> A is a situation, and generally A leads negative (affirmative) situation B,\n> but on the contray to such expectation, affirmative (negative) situation B\n> is true.\n>\n> \"A としては B\" \n> A is a noun, , and generally A has a negative (affirmative) property B, but\n> on the contray to such expectation, A has an affirmative (negative) property\n> B.",

"comment_count": 1,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T07:09:37.287",

"id": "42409",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T14:09:12.617",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-10T14:09:12.617",

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "19219",

"parent_id": "42387",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": -1

},

{

"body": "I think にしては is close to \"considering\" and としては is close to \"as\".\n\nFor example, 彼は英語の先生にしては、優秀だ (He is talented considering he is a English\nteacher.) implies he has an ability other than English, but 彼は英語の先生としては、優秀だ\n(He is talented as a English teacher.) implies the ability of teaching\nEnglish.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T14:48:01.177",

"id": "42422",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T17:50:59.233",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-10T17:50:59.233",

"last_editor_user_id": "5010",

"owner_user_id": "7320",

"parent_id": "42387",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 8

}

]

| 42387 | null | 42422 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42393",

"answer_count": 1,

"body": "A [news\narticle](http://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/easy/k10010830131000/k10010830131000.html)\nis describing the phenomenon of lucky-dip bags in Tokyo libraries:\n\n> どんな本が入っているかは **わからないようになっています** 。いつもは読まない種類の本や読んだことがない作家を知ってもらおうと **考えて**\n> 、去年から始めました。 \n> **It's reached the point where** you don't know what kind of books will be\n> in them. It's expected that you will come to know authors you've never read\n> and book types that you don't normally read, and it started last year.\n\nThe usual translation of \"reached the point that\" for ようになる does not seem to\nwork here. Why would we ever have known what was in a lucky-dip bag? So, what\nis the function of ようになる in this sentence.\n\nAlso, is \"expect\" a valid translation of 考える in this context? I struggled with\nthat part.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-09T22:59:16.267",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42388",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T01:42:17.750",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "7944",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 3,

"tags": [

"grammar"

],

"title": "Confusing use of ようになる",

"view_count": 266

} | [

{

"body": "> 「~~ようになっている」= \"to be (purposely) designed so that ~~\", \"to be designed in\n> such a way that ~~\", etc.\n\nThe TL \"reached the point that\" does not apply here.\n\nThus,\n\n> 「どんな本が入っているかはわからないようになっています。」 means:\n>\n> \"It is (intentionally) designed in such a way that you will not know what\n> books are in (the bag).\"\n\nFinally,\n\n> Also, is \"expect\" a valid translation of 考える in this context?\n\nYes, it is. Here, it means \" _ **to anticipate**_ \", \" _ **to hope**_ \", etc.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T01:42:17.750",

"id": "42393",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T01:42:17.750",

"last_edit_date": "2020-06-17T08:18:27.500",

"last_editor_user_id": "-1",

"owner_user_id": null,

"parent_id": "42388",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 3

}

]

| 42388 | 42393 | 42393 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42400",

"answer_count": 2,

"body": "> また別のときにチェスをしましょう。\n\nThe translation was \"Let's play chess another time.\" But what does また change\nin the sentence? I saw some translations for また, however I couldn't get it.",

"comment_count": 2,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T00:05:45.970",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42389",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T02:39:45.000",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "17380",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 2,

"tags": [

"words"

],

"title": "What does また mean in this sentence?",

"view_count": 1103

} | [

{

"body": "\"Let's play chess _again_ another time\" Where また seems to imply that a game of\nchess was played.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T02:15:39.463",

"id": "42397",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T02:21:58.530",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-10T02:21:58.530",

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "19352",

"parent_id": "42389",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 2

},

{

"body": "First, \"別の時に\", \"別の機会に\", \"今度\", \"次(の時に)\", all of these phrases mean \"next time,\nanother time.\"\n\nI guess you are focusing on the use of \"また\", right?\n\n> When you finish playing chess, you can say \n> \"また今度チェスをしましょう。\"\n\n* * *\n\n> When you meet a person who is famous as the best chess player, and you also\n> have strong confidence in playing chess. You want to play chess with him or\n> her, but you have no time to play chess, then you can say, \n> \"今度チェスをしましょう\" = \"Let's play chess another time.\"\n\nOff course, it's confusing to say \"また今度チェスをしましょう\" = \"Let's again play chess\nanother time.\"\n\nI'm not sure what you are following, but I hope the above my advise could be\nhelpfull for you. If I misunderstood your question, put your question here\nagain.\n\nまた今度ね!",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T02:39:45.000",

"id": "42400",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T02:39:45.000",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "19219",

"parent_id": "42389",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 3

}

]

| 42389 | 42400 | 42400 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42391",

"answer_count": 1,

"body": "I know the translation of the sentence, but I don't understand some\nstructures. Is もし from a verb? And what does いくら mean here?\n\n> 車を運転する時は **いくら注意してもしすぎる** ことはない。",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T01:02:02.197",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42390",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T01:53:40.500",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "17380",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 1,

"tags": [

"words",

"syntax"

],

"title": "I could not understand this sentence entirely",

"view_count": 125

} | [

{

"body": "You are parsing it wrong.\n\n> 車を運転する時はいくら注意してもしすぎることはない。\n\nIn parts,\n\n`車を運転する時は` means \"when you drive a car\" and explains in what circumstances the\nlatter part of the sentence applies.\n\nいくら注意してもしすぎることはない\n\nいくら = how much to / to what degree\n\n注意 has two meanings. Either to warn someone or to be mindful of something.\n\nして = て-form of する\n\nも - this makes it a pattern いくら **Vて** も - \"no matter how much\". In this case,\nroughly \"how careful you are\"\n\nしすぎる = し is the stem of する and すぎる is to do something too much. ~ことはない = there\nis no such thing as ~.\n\nSo for the whole:\n\nWhen driving a car, there is no such thing as being too careful.\n\nor\n\nWhen you're driving a car, you can never be too careful.",

"comment_count": 1,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T01:32:27.457",

"id": "42391",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T01:53:40.500",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-10T01:53:40.500",

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "4091",

"parent_id": "42390",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 5

}

]

| 42390 | 42391 | 42391 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42405",

"answer_count": 2,

"body": "Looking up ある程度 on Weblio [yields a lot of\nphrases](http://ejje.weblio.jp/sentence/content/%E3%81%A7%E3%81%82%E3%82%8B%E7%A8%8B%E5%BA%A6)\nlike\n\n`Xである程度` --> to the extent that something is X\n\nis this to be understood as **`Xである 程度`** or **`X で ある程度`** ?\n\nI don't know if this is a set phrase or not, but what is the function of the で\nin this? Is it で、as in です's て-form, or is it connected to である?\n\nIf I wanted to say a phrase like\n\n> **The degree to which something is expensive is dependent on the market\n> price**\n\nwould I say\n\n> **高価である程度は相場に基づいている?**",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 4.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T01:39:36.907",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42392",

"last_activity_date": "2020-12-25T15:05:08.370",

"last_edit_date": "2020-12-25T15:05:08.370",

"last_editor_user_id": "37097",

"owner_user_id": "10300",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 3,

"tags": [

"grammar",

"translation",

"set-phrases"

],

"title": "Nである程度 ― the degree to which one is N",

"view_count": 419

} | [

{

"body": "First \"ある程度\" means \"on some leve or to some extent.\"\n\n> \"ある程度のお金を使う\" = \"spend a certain amount of money\"\n\n\"ある程度\" of \"である程度\" has different meaning from \"(just)ある程度.\"\n\nThe followings are examples from Weblio,\n\n> 頑固である程度 \"the degree of obstinacy\" \n> 質素である程度 \"the degree of simplicity\"\n\n## \"〇〇である程度\" = \"〇〇である。その程度(level or degree)\"\n\n> \"私の父は頑固である(=私の父は頑固だ)。\"、\"どの程度頑固ですか?\"、”頑固である程度を説明するのは難しいが、強いて言えば「牛のように頑固だ」” \n> \"My father is stubbom.\" \"How stuboom is he?\" \"It's hard for me to explain\n> how stuboom he is, but to stretch a point, he is as stubbom as an ox.\"\n\nEeven through the phrase \"である程度\" is familiar for me, but when I try to make\nexamples using \"である程度,\" I found it's difficult.\n\nThen, the following example is natural.\n\n> \"私の父は頑固である(=私の父は頑固だ)。\"、\"どの程度頑固ですか?\"、”どのくらい(程度)頑固か(を)説明するのは難しい。”\n\nAnyway, you can understand \"である程度\" as one phrase.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T04:07:11.203",

"id": "42404",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T07:54:39.083",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-10T07:54:39.083",

"last_editor_user_id": "9831",

"owner_user_id": "19219",

"parent_id": "42392",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 1

},

{

"body": "ある程度 is a common set phrase that means \"to a certain extent/amount/degree\",\nbut it's not used in this sense in those ~である程度 examples on Weblio. They are\n`[Xである→]程度`.\n\nIn general `(na-adjective) + である程度` can be translated as `the degree of\n~ness`, but I think `(na-adjective) + である程度` is not common. I feel it's a bit\nroundabout. For example, we usually say 危険さの程度, 危険の程度 or even 危険度, instead of\n危険である程度. I don't know why Weblio has this many examples of ~である程度 even though\nthey are far from idiomatic.\n\nLikewise 高価である程度は相場に基づいている sounds weird to me, and I can't help seeing the set\nphrase ある程度 in this sentence (i.e, \"It's expensive, and is more or less based\non the market price\"). Why not simply say 値段の高さは相場に基づいている or even\n価格は相場に基づいている?",

"comment_count": 1,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T04:24:32.127",

"id": "42405",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T04:24:32.127",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "5010",

"parent_id": "42392",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 4

}

]

| 42392 | 42405 | 42405 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42399",

"answer_count": 1,

"body": "The dictionary says that the antonym for 失意 is 得意. But at the same time, the\nantonym for 得意 is 不得意.\n\nAny idea?",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T01:45:02.183",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42394",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T02:37:33.840",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "11192",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 2,

"tags": [

"antonyms"

],

"title": "What is the antonym for 失意?",

"view_count": 143

} | [

{

"body": "The primary meaning of 失意 is _disappointment_ or _disappointed_.\n\n[Dictionary\nsays](http://dictionary.goo.ne.jp/jn/157848/meaning/m0u/%E5%BE%97%E6%84%8F/)\n得意 has several meanings, and there are several antonyms for 得意 for each\nmeaning:\n\n 1. satisfied, content ⇔ **失意** , **がっかり** disappointed\n 2. proud, prideful ⇔ **不名誉** , **面目ない** embarrassed, ashamed\n 3. good at (e.g., tennis, math) ⇔ **不得意** , **苦手** bad at\n\nThat said, the primary meaning of 得意 is now \"be good at\" in modern Japanese.\nThe second meaning is usually expressed with\n[得意気](http://jisho.org/word/%E5%BE%97%E6%84%8F%E3%81%92) (e.g. 得意気な顔), and the\nfirst meaning is almost dead IMO. So I don't feel 得意 is a good antonym for 失意.\n(Judging from examples\n[here](http://dictionary.goo.ne.jp/jn/157848/example/m0u/%E5%BE%97%E6%84%8F/),\n得意 seems to have been used in the first sense until relatively recently\n(approx 100 years ago)).\n\nPerhaps more straightforward antonym for 失意 would be 満足 (satisfaction), 期待\n(expectation), 希望 (hope), or such.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T02:32:22.753",

"id": "42399",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T02:37:33.840",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-10T02:37:33.840",

"last_editor_user_id": "5010",

"owner_user_id": "5010",

"parent_id": "42394",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 2

}

]

| 42394 | 42399 | 42399 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "43198",

"answer_count": 2,

"body": "When [unit tests](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unit_testing) run\nsuccessfully, in English I would say:\n\n> Unit tests are passing.\n\nBut how to say that in Japanese?\n\nMy Japanese colleagues always say something that sounds a bit like\n\"ユニットテストXX(tawli)ます\". For years I have believed it was \"ユニットテストが通ります\" but I am\npretty sure I am wrong since Google only has [two\nhits](https://www.google.co.jp/search?q=%22%E3%83%A6%E3%83%8B%E3%83%83%E3%83%88%E3%83%86%E3%82%B9%E3%83%88%E3%81%8C%E9%80%9A%E3%82%8A%E3%81%BE%E3%81%99%22)\nfor that sentence.",

"comment_count": 3,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T02:13:00.417",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42396",

"last_activity_date": "2017-02-05T02:36:12.110",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-10T05:20:31.863",

"last_editor_user_id": "107",

"owner_user_id": "107",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 4,

"tags": [

"word-requests"

],

"title": "How to say \"unit tests are passing\"",

"view_count": 485

} | [

{

"body": "The verb choice, 通る, is perfectly fine. 通過する is another option (sounds more\nformal). 合格 is less common but acceptable. ユニットテストが及第点 sounds funny to me\nbecause it's too long and [units tests usually have to be 100%\ngreen](https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8D%98%E4%BD%93%E3%83%86%E3%82%B9%E3%83%88).\n\nSince テスト in this context is essentially a program, there are several verb\nusages that may not be familiar to non-developers. For example テストが走る (runs),\nテストが動く (runs), テストが失敗する (fails), テストがこける (fails), テストが転ぶ (fails), テストが死ぬ\n(crashes). And テストが通る (passes) is one of them.\n\nThe problem is about conjugation. ユニットテストが **通ります** is rarely used because 通る\nis a punctual ([instant state-\nchange](https://japanese.stackexchange.com/q/3122/5010)) verb and the subject\nis an inanimate object. What we usually hear are:\n\n * ユニットテストは通ると思います。 I think unit tests will pass.\n * ユニットテストが通りました。 Unit tests have passed (just now).\n * ユニットテストは通るところです。 Unit tests are about to pass.\n * ユニットテストは通っています。 Unit tests have (already) passed.\n\nDo you really hear ユニットテストが通ります at the office often? It may be said by a\nperson who has been watching the progress meter of the test runner. If he has\nto repeatedly report the completion of the tests to someone else, he might say\nユニットテストが通ります. (\"(Everyone,) Unit tests passing (in a few seconds)!\").\n\n**EDIT:** To clarify, if you want to say a certain build/test has passed and\nthus the status is green (), テスト/ビルドが通っ **ている** is the\nright choice, not 通る.",

"comment_count": 3,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T02:55:07.473",

"id": "42401",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T06:58:00.780",

"last_edit_date": "2017-04-13T12:43:44.260",

"last_editor_user_id": "-1",

"owner_user_id": "5010",

"parent_id": "42396",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 4

},

{

"body": "Although I think naruto's answer is valid and sufficient, here's some\nadditional research I did. Below, I'm simply stating that 「ユニットテスト」+「通る」 are\nfrequently used together, disregarding the difference between\n「通る」「通ります」「通っている」 etc.. Sorry to be late.\n\n## 1. 「テストが通る」 is commonly used for \"tests are passing\" in coding contexts.\n\nI consider myself to be a casual hobbyist programmer (whose mother tongue is\nJapanese) and I can confirm that 「テストが通る」 is a valid and the most preferred\ncollocation for tests passing. What form to use is detailed in nauto's answer,\nand I only want to add 「これでテストが通ります」 after fixing problems -- The tests are\npassing _with this [patch]_ /This patch makes the test pass. When tests fail,\nit's テストが「落ちる」, 「こける」, 「失敗する」 or sometimes 「死ぬ」.\n\nIn fact, [google search for\n\"テストが通る\"](https://www.google.co.jp/search?q=%22%E3%83%86%E3%82%B9%E3%83%88%E3%81%8C%E9%80%9A%E3%82%8B%22)\nhas 47300 results as of today and the top 20 results, 100 probably, are all in\ncoding context. After [restricting the domain to\ngithub.com](https://www.google.co.jp/search?q=%22%E3%83%86%E3%82%B9%E3%83%88%E3%81%8C%E9%80%9A%E3%82%8B%22+site%3Agithub.com&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8)\nit still has 314 results.\n\n## 2. 「通る」 is among the three verbs most frequently used with 「ユニットテスト」 in\ntwitter.\n\nWe can assume the same for unit tests --- there's no reason to choose a\ndifferent verb for unit tests specifically! However, as you have mentioned,\nexamples of \"ユニットテストが通る\" seems to be a bit more difficult to find in google.\nGoogle says it has 1470 results of\n[\"ユニットテストが通る\"](https://www.google.co.jp/search?q=%22%E3%83%A6%E3%83%8B%E3%83%83%E3%83%88%E3%83%86%E3%82%B9%E3%83%88%E3%81%8C%E9%80%9A%E3%82%8B%22&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8)\nbut actually won't show me more than 22 results; only 7 hits for\n[\"ユニットテストが通\"](https://www.google.co.jp/search?q=%22%E3%83%A6%E3%83%8B%E3%83%83%E3%83%88%E3%83%86%E3%82%B9%E3%83%88%E3%81%8C%E9%80%9A%22&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8).\n\nI searched for \"ユニットテスト\" in twitter, where many Japanese tech people are\nactive, and counted which verb is used together. With 65 most recent hits, the\nresult was as follows:\n\n 1. 書く (ユニットテストを書く・書ける・書いた, etc.) _write_ : 13 times \n 2. ない (ユニットテストがない) _there's no/we don't have_ : 9 times\n 3. 通る (ユニットテストが通る・通らない・通った, etc.) _are passing_ : 8 times\n 4. できる _[we] can run_ : 4 times\n 5. 必要 _[we] need_ : 3 times\n 6. and 24 others with less than 2 hits each, totalling 29\n\nI think we can now feel safe :)\n\n* * *\n\nSo why \"ユニットテストが通る\" is so much less common in google? My speculation is that\nwe usually want to know if all tests are passing, and if not, which test\nexactly is failing. We usually don't care if specific kind of tests are\npassing (\"Are this kind of tests passing?\" isn't something we usually ask).\nThis means that the _\"unit\"_ part is actually redundant in many cases. I\nsuspect that ユニット part hence tends to be just omitted in Japanese, perhaps\nbecause ユニットテスト (yunitto tesuto, key-stroke wise) feels lengthy.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-02-05T02:36:12.110",

"id": "43198",

"last_activity_date": "2017-02-05T02:36:12.110",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "4223",

"parent_id": "42396",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 2

}

]

| 42396 | 43198 | 42401 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": null,

"answer_count": 3,

"body": "Hi I want to write a congrats message to my Japanese friend and I want to tell\nhim this:\n\n```\n\n Happy birthday\n \n I wish you so many more wonderful experiences \n \n and have a lot of fun this day\n \n```\n\nObviously the first line will be:\n\n```\n\n お誕生日おめでとう\n \n```\n\nAnd the second line will be:\n\n```\n\n もっと素晴らしいことがあるといいです\n \n```\n\nAnd the third line something like this:\n\n```\n\n そして楽しい日を過ごしてね\n \n```\n\nSo I think that the first and third lines are relatively correct, but I really\nhave my doubts on the second line. What do you think? Is there another way to\nsay the same thing?",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T04:51:01.083",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42406",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T12:54:54.147",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-10T21:29:16.177",

"last_editor_user_id": "13961",

"owner_user_id": "13961",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 0,

"tags": [

"grammar",

"syntax"

],

"title": "Some congratulations phrases for birthday?",

"view_count": 435

} | [

{

"body": "I think もっと(たくさん)素晴らしいことがあるといいです isn't unnatural and it is literally\ntranslated as \"もっとたくさん素晴らしい経験(体験)をしてね.\"\n\nThe other option I came up is\"もっとたくさん素晴らしい出来事があるといいね.\".",

"comment_count": 2,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T16:13:23.567",

"id": "42423",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T16:18:33.717",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-10T16:18:33.717",

"last_editor_user_id": "7320",

"owner_user_id": "7320",

"parent_id": "42406",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 2

},

{

"body": "This may just be my personal style of speaking, but for the second line I'd\nsay\n\n> 今年素晴らしい経験がたくさんありますように\n\nor\n\n> 今年が素晴らしい体験いっぱいの一年になりますように\n\nAlso, for the third line I'd say 「楽しい一日」 instead of just 「楽しい日」, but that's\nsomething minor.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T16:53:00.090",

"id": "42424",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T16:53:00.090",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "78",

"parent_id": "42406",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 1

},

{

"body": "```\n\n もっと素晴らしいことがあるといいです\n \n```\n\nIt does not sound odd, but your translation is incorrect... In English, it is:\n\n> I hope more wonderful things happen (to you).\n\nI would translate:\n\n> * もっと素晴らしい経験(体験)がありますように (prayer)\n> * もっと素晴らしい経験(体験)ができるといいね\n>",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-11T12:54:54.147",

"id": "42438",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T12:54:54.147",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "14627",

"parent_id": "42406",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 0

}

]

| 42406 | null | 42423 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42412",

"answer_count": 1,

"body": "I'm wondering if you guys have any in-depth answers/links regarding:\n\n-multiple adjectives modifying one noun (I'll go into the specifics below, I don't mean just the て form conjugations)\n\n-order of adjectives and/or の when used in sequence\n\nAdjective order:\n\n 1. In English, we say “big black bear” but not “black big bear.” Is there a similar preferred order for adjectives used together to modify the same noun? If certain orders are preferred, does it have anything to do with whether the adjective is a「な」or「い」form? (ex. 静かなかわいい子 vs. かわいい静かな子) Or does it have to be 可愛 **く** 静かな子?\n\n 2. What other sentence structures/conjugations can be used to link adjectives in a relative clause to modify the same noun? (Not structures like: 彼はダサくてきもい。)\n\nWhen の comes into the equation:\n\n 1. When a lot of のs are chained together, which modifies which? (ex. In「理想の店員の態度」, does it break down into 理想の **店員の態度** where “ideal” modifies “store clerk’s attitude” to mean the ideal attitude of a store clerk or into **理想の店員** の態度 where “ideal store clerk” modifies “attitude” to mean the attitude of an ideal store clerk?) I know in this example it doesn’t make much of a difference, but in some cases it would, like 最初の日本の専門家 (Disregard the fact there are better ways of saying the same thing). Does that mean “the first **specialists in/of Japan** ” _or_ “the specialists of **early Japan**?” Basically, is it open to interpretation or is there generally an order of which のs are considered first? such as AのBのCのD being _Aの_ [Bの( **CのD** )]\n\n 2. What about when using の and an adjective to modify the same noun? (ex. 天来の美しい歌、美しい天来の歌)",

"comment_count": 2,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T05:04:34.627",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42407",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T08:00:56.690",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "19355",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 9,

"tags": [

"grammar",

"usage",

"adjectives"

],

"title": "Order of multiple nouns and adjectives modifying the same noun",

"view_count": 888

} | [

{

"body": "We can say both 静かなかわいい子 and かわいい静かな子. かわいい and 静かな are attributive form and\nthey modify 子(a noun). You can also say かわいく静かな子 and 静かでかわいい子 and the former\nadjective is 連用形(conjunctive form) and modify the adjective after it. They are\nall the same meaning.\n\n理想の店員の態度 can mean two ways as you said but I feel it indicates \"the ideal\nattitude of a store clerk.\" than the another. If you want to make sure the\nmeaning of \"the attitude of an ideal store clerk\", it would be\n\"理想の店員がする(行う)態度.\n\n最初の日本の専門家 usually means “the first specialists in/of Japan” because 最初の日本\nrarely means \"early Japan\" but 初期の日本 means it. In addition, even if you change\nthe order of 日本の and 最初の, the meaning is the same, but you can't change the\norder of 日本の and 家の in 日本の家の専門家 because 家の日本 don't make sense. That is to say,\nwhen you change the order, there are the cases that the meaning didn't change\nlike 初期の日本, there are the cases that it doesn't make sense like 日本の家 and there\nare the cases that the meaning changes like 英語の先生.\n\nFor example, the order of the noun can't be changed in 私の家の庭の木の下の穴(the hole\nunder the tree in the garden of my house) because the each noun modifies a\nimmediate noun after it.\n\nWe can say both 天来の美しい歌 and 美しい天来の歌 as the same meaning but 天来 isn't common.",

"comment_count": 4,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T10:24:33.237",

"id": "42412",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T08:00:56.690",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-11T08:00:56.690",

"last_editor_user_id": "7320",

"owner_user_id": "7320",

"parent_id": "42407",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 2

}

]

| 42407 | 42412 | 42412 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42414",

"answer_count": 2,

"body": "> 忘れてて良いのに\n\nI understand this as: \"You should forget about it\"\n\nBut what does のに do?",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T07:04:26.913",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42408",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T00:46:05.347",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "11827",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 4,

"tags": [

"grammar"

],

"title": "What does のに mean at the end of this sentence?",

"view_count": 3329

} | [

{

"body": "I can suppose the following situation.\n\nA helped B out of his (her) hard situation.\n\nB is one of the best A's friends, and A wants to be kind without being\npatronizing.\n\nHowever, every time when B meets A, B shows his (her) thanks.\n\nThen A says \"忘れていいのに\"\n\nThe full sentence could be \"まだあなたは感謝を忘れないんですね。私は忘れていいと思っているのに(どうぞ忘れてください)。\" =\n\"You still owe a huge debt to it、but I sincerely want have you forget it.\"\n\n\"忘れていいのに・・・\" implys such nuans.",

"comment_count": 2,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T07:58:05.580",

"id": "42410",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T00:46:05.347",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-11T00:46:05.347",

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "19219",

"parent_id": "42408",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": -1

},

{

"body": "のに is a conjunction that corresponds to \"even though ~\" or \"despite ~\".\n\n`(clause A)のに(clause B)` = `although A, B`.\n\nUnlike けど, it often (but not always) is followed by something\nregrettable/disappointing. [Examples on\nJGram](http://www.jgram.org/pages/viewOne.php?tagE=noni).\n\nThe latter clause is often omitted, and it implies the reality is something\nregrettable and contrary to the Clause A.\n\n`~のに。` = `although ~, (something contrary)`, `A, but...`, `I wish ~`.\n\nSo 忘れてて良いのに means \"You could have left it (although, in reality, you recalled\nand mentioned it)\".\n\nExamples:\n\n> * こんなに美味しいのに。 It's really delicious (and I wonder why you don't want to\n> eat it)!\n> * そんなに賢いのに。 You are such a smart boy (and I don't understand why you did\n> such a silly thing)!\n> * もっと頑張れば良かったのに。 You should have worked harder.\n> * 空を飛べたらいいのに。 I wish I could fly.\n>\n\nSee also:\n\n * [How and when to use のに(=noni) - Maggie Sensei](http://maggiesensei.com/2012/06/20/how-and-when-to-use-%E3%81%AE%E3%81%ABnoni-request-lesson/)\n * [Meaning and level of 死ねばいいのに](https://japanese.stackexchange.com/q/181/5010)",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T12:37:06.893",

"id": "42414",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T12:37:06.893",

"last_edit_date": "2017-04-13T12:43:44.397",

"last_editor_user_id": "-1",

"owner_user_id": "5010",

"parent_id": "42408",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 12

}

]

| 42408 | 42414 | 42414 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42417",

"answer_count": 2,

"body": "I am writing about the language and I wish to say, that the language can be\nlearnt best, when you can visit it's country, so you could master it by:\n\n> \"getting through different situations\" or \"experiencing through different\n> situations\"\n\nI came up with 「 **様々な【さまざまな】状況【じょうきょう】を通して【とおして】経験【けいけん】すること** 」, but I think\nthere are much more natural ways of expressing this idea. Also, I am not sure,\nif the word 状況【じょうきょう】as for \"situation\" fits well here...\n\nThank you in advance!",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T13:09:19.033",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42415",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-16T20:47:13.700",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-16T20:47:13.700",

"last_editor_user_id": "19357",

"owner_user_id": "9364",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 6,

"tags": [

"translation"

],

"title": "How to say \"Getting/experiencing through different situations\"?",

"view_count": 2080

} | [

{

"body": "> 「場数{ばかず}を踏{ふ}む」\n\nis the first expression that came to mind.\n\n「様々な状況を通して経験する」 is grammatical and it makes perfect sense, but it is wordy and\nit sounds as if it were directly translated.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T13:16:33.423",

"id": "42416",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T13:16:33.423",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": null,

"parent_id": "42415",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 6

},

{

"body": "Your attempt is good, but it can be improved a bit more.\n\nAs 「[経験]{けいけん}する」 is a transitive verb, it's a little bit strange it doesn't\nhave an object.\n\nYou can say 「[経験]{けいけん}を[積]{つ}む」 to mean \"gain experience\" without mentioning\nwhat kind of experience they have. The resulting sentence 「\n**[様々]{さまざま}な[状況]{じょうきょう}を[通]{とお}して[経験]{けいけん}を[積]{つ}むこと** 」 seems no problem\nto me.\n\nAnother option is to say 「[様々]{さまざま}な[状況]{じょうきょう}を[経験]{けいけん}すること」 which\nliterally means \"to experience different situations.\"\n\n* * *\n\nLastly, your word choice of 「[状況]{じょうきょう}」 is very good. Also, 「[場面]{ばめん}」 is\nacceptable here.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T13:17:43.700",

"id": "42417",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T14:56:05.503",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-10T14:56:05.503",

"last_editor_user_id": "17890",

"owner_user_id": "17890",

"parent_id": "42415",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 4

}

]

| 42415 | 42417 | 42416 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": null,

"answer_count": 1,

"body": "I have written the below sentence to say that \"due to feedback on A, fixes are\nrequired in B also, so we will do the required modifications'.\n\n> Aのフィードバックを確認致しました上、それに応じてBにも修正する箇所が発生しましたので、当該修正に対応させて頂きます。\n\nIs `確認致しました上` incorrect here? I am trying to say \"Upon checking X, we found\nthat Y needs to be fixed as well'",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T13:26:08.560",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42418",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T14:37:19.937",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-10T13:56:41.810",

"last_editor_user_id": "4091",

"owner_user_id": "19360",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 1,

"tags": [

"translation"

],

"title": "What is the correct usage for 確認致しました上?",

"view_count": 89

} | [

{

"body": "「V + 上」 has two major meanings. One is temporal order: \"then\" or \"after\". The\nother is \"in addition\". Two events connected with 「上」 is rather independent of\neach other.\n\nSo your sentence would mean \"I checked the feedback on A. In addition, I found\n...\"\n\nMaybe this is not what you want. You should say 「確認致しました **所** 」.\n\n「Vした + 所」 is basically translated as \"when\". Its nuance is \"I did V and what I\ngot/found is ...\", which matches this situation.",

"comment_count": 2,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T14:37:19.937",

"id": "42421",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T14:37:19.937",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "17890",

"parent_id": "42418",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 2

}

]

| 42418 | null | 42421 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42420",

"answer_count": 2,

"body": "I have problem understanding the following sentence from the lower right\npanel:\n\n> そう思{おも}ってあわてて殺虫剤{さっちゅうざい} **たいたら** 私{わたし}がいられなくなって\n\n殺虫剤 is pesticide, but I don't know how to parse たいたら. My bad guess is that\nit's a conjugation of たく but I can't go further. There is no たく that seems to\nmake sense in this context.\n\nAnother question is 私がいられなくなって --- I'm not quite sure how to translate this.\n\"I can't be here\"?\n\n[](https://i.stack.imgur.com/5oJ9K.jpg)",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 4.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T14:09:40.753",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42419",

"last_activity_date": "2019-12-04T14:24:17.537",

"last_edit_date": "2019-12-04T14:13:29.667",

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "4295",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 6,

"tags": [

"grammar",

"translation",

"manga"

],

"title": "What is 殺虫剤たいたら?",

"view_count": 418

} | [

{

"body": "The verb here is 「焚{た}く」 meaning \"to burn\" as in \"to burn incense\". The kind\nof insecticide we are talking about actually diffuses a ton of smoke.\n\nWatch this short video and you will know exactly why you could not stay in\nyour house for at least a few hours after setting off some types of\n殺虫剤{さっちゅうざい}.\n\n<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3nDXTyB6MW8>\n\nLuckily, the video title contains our verb in question -- 「バルサンを焚{た}いてみました。」.\nバルサン is the name of the insecticide.",

"comment_count": 1,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 4.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T14:15:51.793",

"id": "42420",

"last_activity_date": "2019-12-04T14:24:17.537",

"last_edit_date": "2019-12-04T14:24:17.537",

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": null,

"parent_id": "42419",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 11

},

{

"body": "\"[焚]{た}く\" means to burn, make a fire, like kindle firewood and coal. \"[炊]{た}く\"\nmeans to boil, like boil water in the boiler, or cook, like cook rice.\n\nActually you cannot burn insecticides such as being sold by the name of\nBarusan - a rat mite-cite. But when you add water to Barusan up to the\ndesignated line inside the container, it erupts white gas like a smoke screen\nas if something burning.\n\n“いられなくなって” means “I cannot stay there.” If you set up Barusan in your living\nroom or bedroom and once it starts to smolder, you got to rush out of the\nroom, otherwise you’ll be choked.\n\nPlease note that \"[焚]{た}く\"and \"炊{た}く\" are different words, though phonetically\nsound the same.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-13T04:56:52.793",

"id": "42489",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-16T16:06:16.463",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-16T16:06:16.463",

"last_editor_user_id": "9831",

"owner_user_id": "12056",

"parent_id": "42419",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 0

}

]

| 42419 | 42420 | 42420 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42427",

"answer_count": 2,

"body": "I couldn't understand 入って **なかった** , what verb is it after 入って?\n\n> で、帰ったときに携帯はかばんに **入ってなかった** だろう?",

"comment_count": 1,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T22:36:32.517",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42426",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T23:01:35.440",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "17380",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 1,

"tags": [

"meaning",

"verbs"

],

"title": "What does 入ってなかった mean?",

"view_count": 996

} | [

{

"body": "「入{はい}ってなかった」=「入って **い** なかった」\n\nIn informal speech, that 「い」 is very often omitted.\n\nThat is 「入る + いる + ない」 in the past tense **_state_** , not **_action_**.\n\n> \"And then, when you returned home, your cellphone was not in your bag,\n> right?\"",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T22:58:21.520",

"id": "42427",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T22:58:21.520",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": null,

"parent_id": "42426",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 4

},

{

"body": "入ってなかった is the negative past form of 入ってある. The -てある form is used to indicate\nthat \"something has been done to something and the resultant state remains\"\n(from Makino Dictionary of Japanese Grammar). The translation of your sentence\nwould be:\n\n> So, when you came back the phone was missing from your bag, right? (implying\n> that someone took it)\n\nHere's an example to understand the difference between -てある and -ている:\n\n窓が開いている -> The window is open. (no agent or reason implied)\n\n窓が開けてある -> The window is open (because someone opened it).\n\nCheck [this](https://japanese.stackexchange.com/q/5505/17797) and\n[this](https://japanese.stackexchange.com/q/14760/17797) question to learn\nmore about -てある and -ている.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-10T23:01:35.440",

"id": "42428",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-10T23:01:35.440",

"last_edit_date": "2017-04-13T12:43:43.857",

"last_editor_user_id": "-1",

"owner_user_id": "17797",

"parent_id": "42426",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 1

}

]

| 42426 | 42427 | 42427 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42433",

"answer_count": 2,

"body": "For my understanding, the consequential clause would be a complete sentence\nuntil I faced the following conditional sentence.\n\n> 使用できる時間が極端に短くなったら、 **バッテリーパックの寿命です** 。\n\nCan a consequential clause after a 「たら」-clause be a noun clause? Or is this an\nexception?",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-11T02:35:13.970",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42431",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T07:32:26.903",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-11T02:40:28.700",

"last_editor_user_id": "5010",

"owner_user_id": "9559",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 1,

"tags": [

"grammar",

"conditionals"

],

"title": "Question about consequential clause after conditional clause using 「たら」",

"view_count": 119

} | [

{

"body": "たら is basically just a \"if\".\n\n> If A then B.\n\nB can be pretty much anything depending on the context.\n\n> If you go -> I go too.(verb) \n> If it grows -> it's a plant!(noun)",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-11T02:51:20.750",

"id": "42432",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T02:51:20.750",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "18142",

"parent_id": "42431",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 0

},

{

"body": "バッテリーパックの寿命です fully qualifies as a main clause of this sentence. Its subject,\nwhich is omitted, is それ, vaguely referring to the situation previously\nmentioned. Subjects are omitted all the time in Japanese sentences, and there\nis nothing special in this case. Technically, the last half of this sentence\nis not a noun clause, because it has no nominalizer and ends with です, a copula\n(aka linking _verb_ ).\n\n寿命 in this context is _end-of-life_ rather than _lifespan_. 寿命だ/寿命です does not\nmean \"It's a lifespan\" here, but it means \"is reaching / has reached the end\nof one's life,\" \"is near one's end,\" \"is dying a natural death,\" \"is on one's\nlast legs,\" etc.\n\nIn other words, 寿命 is sometimes used as a [no-\nadjective](https://japanese.stackexchange.com/a/2771/5010), usually in\ncombination with もう.\n\n> * その時計はもう寿命だ。 \n> The watch has reached the end of its life (and thus not repairable).\n> * また止まったの? それは時計の寿命だよ。 \n> It stopped again? That means the watch has reached the end of its life.\n> * 彼はもう寿命です。\n> * もう寿命のスマートフォン a smartphone near the end of its life / on its last legs\n>\n\nSee: [「バッテリが寿命です。」は英語で](http://okwave.jp/qa/q1533929.html)",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-11T02:52:04.087",

"id": "42433",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T07:32:26.903",

"last_edit_date": "2017-04-13T12:43:44.740",

"last_editor_user_id": "-1",

"owner_user_id": "5010",

"parent_id": "42431",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 3

}

]

| 42431 | 42433 | 42433 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42439",

"answer_count": 2,

"body": "I am writing the following sentence:\n\nサン・パウロに日本人がいっぱいいるから。。。よかったですね!\n\nAnd I'd like to know if 幾人も could be a more respectful/more natural\nreplacement for 一杯, and whether I should be using kanji.",

"comment_count": 1,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-11T08:10:35.813",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42434",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T16:19:26.683",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": "19369",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 1,

"tags": [

"kanji",

"politeness",

"counters",

"idioms"

],

"title": "幾人も or 一杯? Kanji or hiragana?",

"view_count": 158

} | [

{

"body": "幾人も isn't a more respectful/more natural replacement for 一杯 and it is a very\nliterary word, so we rarely say it in conversation.\n\nYou can put いっぱい into たくさん, かなり, 大勢. いっぱい written in hiragana is more common\nthan the one written in kanji.",

"comment_count": 2,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-11T09:07:51.977",

"id": "42435",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T16:19:26.683",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-11T16:19:26.683",

"last_editor_user_id": "7320",

"owner_user_id": "7320",

"parent_id": "42434",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 1

},

{

"body": "> 「サン・パウロ **に** 日本人がいっぱいいるから。。。よかったですね!」\n\nThis sentence is OK. The only thing I would change to make it more natural\nwould be the 「に」. Using 「には」 would make it far more natural.\n\n> And I'd like to know if 幾人{いくにん}も could be a more respectful/more natural\n> replacement for 一杯{いっぱい}, and whether I should be using kanji.\n\nUsing 「幾人も」 in this context would be a bad idea. Why? Because it only means\n\"many\" mostly when the number is a dozen or two **_at the most_**. São Paulo\nhas about a million Japanese and Japanese Brazilians, correct? That is\ndefinitely **_way_** too many to call 幾人も.\n\nI would not worry about writing 「いっぱい」 using kanji. Your sentence is already\nvery informal with the use of 「から」 and 「よかったですね!」. 「から」 is more informal than\nmany J-learners seem to think.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-11T13:20:21.473",

"id": "42439",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T14:04:42.063",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-11T14:04:42.063",

"last_editor_user_id": "9831",

"owner_user_id": null,

"parent_id": "42434",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 2

}

]

| 42434 | 42439 | 42439 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42437",

"answer_count": 1,

"body": "I know that _sonkeigo_ for someone's home is お宅, but since the word オタク has a\nquite negative connotation, I am worried that お宅 might not be appropriate,\nespecially in spoken language (because there is no way to differentiate お宅 vs\nオタク). Hence, is there any alternative to お宅, or do I have to use this word\nreally carefully?",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-11T12:13:08.923",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42436",

"last_activity_date": "2021-11-24T12:54:03.880",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-12T06:59:47.573",

"last_editor_user_id": "7810",

"owner_user_id": "19346",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 2,

"tags": [

"word-choice",

"usage",

"connotation"

],

"title": "Referring to someone's home in sonkeigo",

"view_count": 194

} | [

{

"body": "> I am worried that お宅 might not be appropriate, especially in spoken language\n> (because there is no way to differentiate お宅{たく} vs オタク).\n\nThat is not true at all because people can always tell which one you meant\nfrom the context of the conversation.\n\nI could not think of a single example where there could be that kind of\nconfusion because the difference in meaning is just huge between the two\nwords.\n\nBesides 「お宅{たく}」, you can use 「ご自宅{じたく}」 or 「お住{す}まい」. All are good words to\nknow.\n\nThere exist bigger words such as 「尊宅{そんたく}」, 「尊家{そんか}」, etc., but those are\nrarely, if ever, used.",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 4.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-11T12:26:23.503",

"id": "42437",

"last_activity_date": "2021-11-24T12:54:03.880",

"last_edit_date": "2021-11-24T12:54:03.880",

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": null,

"parent_id": "42436",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 6

}

]

| 42436 | 42437 | 42437 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42445",

"answer_count": 1,

"body": "すみません。母語サイトに帰って来てしまいました。\n\n自分のビジネスサイトをSEO強化させる為にSEOプラグインで有名な[Yoast\nSEO](https://ja.wordpress.org/plugins/wordpress-\nseo/)を使い始めたら元がアメリカ製のプラグインなので日本語化が不十分でいつの間にか英→日翻訳を助けるようになりました。(日本語化率現在56%)。その中で英語でlocationという言葉[](https://i.stack.imgur.com/8y5nN.jpg)にぶち当たってしまったのですが適当な言葉は何でしょう。教えて下さい(m_m)。(個人的にはドメインかと推測しています。)\n\n* * *\n\nI started using a SEO plug-in, called Yoast SEO, which is a tool to enhance\nthe internal structure inside your or business homepage. Because the plug-in\nis ( was ) developed by Americans, however very popular, though the language\nfitness to Japanese is yet 56%, I started helping translation. However, I am\nnot sure how I should translated the word \"location\", which you can see at the\npicture, could anyone have any idea what this could mean. ( I personally\nguessing this could be a \"domain\" ). Thank you and I know I am at the risk of\nthis being busted.",

"comment_count": 8,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-11T14:51:27.580",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42440",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-12T11:20:15.983",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-12T11:20:15.983",

"last_editor_user_id": "1628",

"owner_user_id": null,

"post_type": "question",

"score": 3,

"tags": [

"english-to-japanese"

],

"title": "SEOプラグインにおけるlocationは何を意味するのでしょうか? What does \"location\" mean within a SEO plugin",

"view_count": 279

} | [

{

"body": "Yoast SEO の一部として [Local SEO](https://yoast.com/wordpress/plugins/local-seo/)\nという機能があり、それの翻訳をしているようですね。これは、ビジネスの行われている地域(国・都市)に基づいて検索効率が高まるよう、色々してくれるというもののようです。Googleで「クリーニング店」とか「バッティングセンター」とか「ヨガ教室」とかで検索すると、近くにある実店舗の一覧が地図付きで出てきますよね、その機能に関するSEOをやってくれるプラグインです。煎じ詰めると[この仕組み](https://www.suzukikenichi.com/blog/google-\nrecommends-using-schema-org-for-location-pages/)が関係しています。\n\nということで、locationは、ネット上のURLとかドメインのことではなく、地理的な「場所」「位置」のことだと思います。\n\n[ヘルプ](https://kb.yoast.com/kb/configuration-guide-for-local-\nseo/)を見る限り、locationとは「ビジネス名(店舗名)」とか「住所」とか「電話番号」とかを含む登録項目のようであり、複数のlocationを管理できるようです。つまりlocationとは、具体的には個々の支店とか営業所とか事務所とかのことを指しています。複数の支店を登録させているような文脈で、「位置を追加して住所を登録する」とか「場所の削除」とか言われると逆に分かりづらい気がします。ですので個人的には思い切って「\n**ロケーション** 」で統一してしまうのがわかりやすいのでは、と思います。漢字がいいなら「 **場所情報** 」でもいいかもしれません。\n\n一般的に、ソフト自体の機能に習熟しないままに逐語訳させられると、どんなに語学力がある人でもミスをしてしまいます。まずはそのプラグインのヘルプを読み込み、実際に使い込んで、「location」がどんな場面で使われているのか理解してから訳すべきだと思います。",

"comment_count": 1,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-11T17:12:42.153",

"id": "42445",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T17:58:00.000",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-11T17:58:00.000",

"last_editor_user_id": "5010",

"owner_user_id": "5010",

"parent_id": "42440",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 5

}

]

| 42440 | 42445 | 42445 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42442",

"answer_count": 1,

"body": "> ufotableが書き上げた脚本を、奈須きのこが原作者としてリライトしたのが本稿である。\n\nMy question is according to this sentence what happens to the written text of\nthe film.\n\nI found another sentence from the author himself in [his\nblog](http://www.typemoon.org/bbb/diary/log/201506.html)\n\n> #25の制作は「ほぼオリジナルなので、まずは原作サイドで書くべし」と始まりました。そしてできあがったきのこによる脚本モドキを前に頭を抱える制作陣。",

"comment_count": 0,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 4.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-11T15:00:24.477",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42441",

"last_activity_date": "2022-08-10T00:48:27.527",

"last_edit_date": "2022-08-10T00:48:27.527",

"last_editor_user_id": "30454",

"owner_user_id": "19329",

"post_type": "question",

"score": 3,

"tags": [

"meaning"

],

"title": "ufotableが書き上げた脚本を、奈須きのこが原作者としてリライトしたのが本稿である。",

"view_count": 224

} | [

{

"body": ">\n> 「ufotableが書{か}き上{あ}げた脚本{きゃくほん}を、奈須{なす}きのこが原作者{げんさくしゃ}としてリライトしたのが本稿{ほんこう}である。」\n\nTwo different works are mentioned here:\n\n1) ufotableが書き上げた脚本 (\"the script written by Ufotable\")\n\n2) 奈須きのこが原作者としてリライトした **の** (\"(what/the thing) Kinoko Nasu has rewritten as\nthe (original) author\") 「の」 is a nominalizer.\n\nAnd please note that the subject of the sentence is 2) and that **_2) is based\noff of 1)_**.\n\n> \"This is the manuscript where Kinoko Nasu, as its author, has rewritten\n> based off of the script written by Ufotable.\"",

"comment_count": 2,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-11T15:47:41.543",

"id": "42442",

"last_activity_date": "2017-01-11T15:47:41.543",

"last_edit_date": null,

"last_editor_user_id": null,

"owner_user_id": null,

"parent_id": "42441",

"post_type": "answer",

"score": 5

}

]

| 42441 | 42442 | 42442 |

{

"accepted_answer_id": "42444",

"answer_count": 2,

"body": "I have seen kanji characters on maps referencing Germany, China, Italy, the\nUnited States of America, and various other countries, but many are written in\nkatakana. Is there a reason for this?",

"comment_count": 1,

"content_license": "CC BY-SA 3.0",

"creation_date": "2017-01-11T15:52:04.307",

"favorite_count": 0,

"id": "42443",

"last_activity_date": "2022-10-04T18:01:57.120",

"last_edit_date": "2017-01-11T16:26:11.087",

"last_editor_user_id": "18435",

"owner_user_id": "18435",